In the movie Arrival, there’s a scene where Ian reads from Dr. Louise Banks’ book: “Language is the foundation of civilization,” she wrote. “It is the glue that holds people together. It’s the first weapon drawn in a conflict.”

Arrival is based on Ted Chiang’s “A Story of Your Life” which is about the difference between written and spoken language, and its implications. It’s fascinated me ever since I watched/read the works.

It’s important to me because with the advent of generative AI, I think we have a chance to reimagine how we communicate with computers.

Voice as an input is an especially interesting area where we can reimagine human <> computer interaction. Voice is more important than ever now that computers can now hold natural language conversations, but voice is underdeveloped as a digital medium relative to the billions of people using voice for computing today – 1 in 5 people uses a voice assistant today.

With every technology leap shortcuts, buttons, and symbols emerge to quickly help us streamline communication and convey meaning faster.

In Arrival/Ted Chiang’s story, they give the example of this: , a sign which means “Not Allowed”. Only the written words are a representation of speech however, the first is a symbolic expression, a visual syntax.

Some of my favorite symbols include:

And we use so many more in our everyday digital lives:

To properly develop voice as a computer medium, we need “voice buttons or voice shortcuts.” This idea was shared by Julian Lehr in his cheeky article titled “the case against conversational interfaces.”

Norm Cox, the person credited with inventing the “hamburger” menu icon described his creation saying, “Its graphic design was meant to be very ‘road sign’ simple, functionally memorable, and mimic the look of the resulting displayed menu list. With so few pixels to work with, it had to be very distinct, yet simple.”

Buttons, symbols and shortcuts emerged to speed up digital interactions. To send and receive information faster to/from the computer. This works because symbols are a form of data compression. Rather than type out a long prompt in the command line, GUIs were invented to increase computer interaction speed.

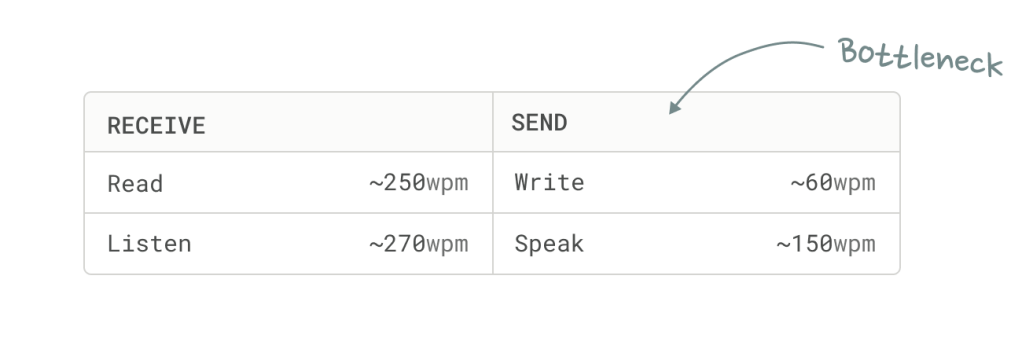

My strong belief is that voice’s primary value is as an input mechanism, not output. That’s because voice is where we gain the greatest speed advantage.

If you’re a WhatsApp voice-note user, you’ve likely experienced the inconvenience of listening to a long voice note. Even if you are prone to leave long ones yourself. Voice is slow as a data consumption mechanism.

For older generations and instances where written prose is needed (work) voice buttons will solve the computer interaction bottleneck, first for typing, and later once we have autonomous agents that can actually execute tasks – controlling the full display.

Typing is the nearest term opportunity since it has the greatest replacement value. We are already seeing tools like Willow and Wispr emerge to solve this need.

The question is, how will voice buttons emerge? The answer lies in understanding the inherent properties of 1) voice as a tool and 2) what voice is best at replacing: typing.

Properties of voice as a tool:

- Rate – cadence

- Pitch

- Volume (a crescendo to decresendo)

- Timber – tone, resonance, clarity

Properties of typing:

- Font type

- Font size

- Spacing – letter, line, paragraph

- Positioning – centered, right, left

- Punctuation

- Capitalization / Case

Voice has some inherent advantages in communicating greater density of information than typing – primarily, emotion.

I can think of many examples of how voice shortcuts could increase the speed in which we interact with a computer.

Here’s just a few Voice Buttons I can think of for replacing typing:

- When I say “ellipses” to my computer, I don’t want it to write “ellipses”….I want it to write dot dot dot as I did earlier in this sentence.

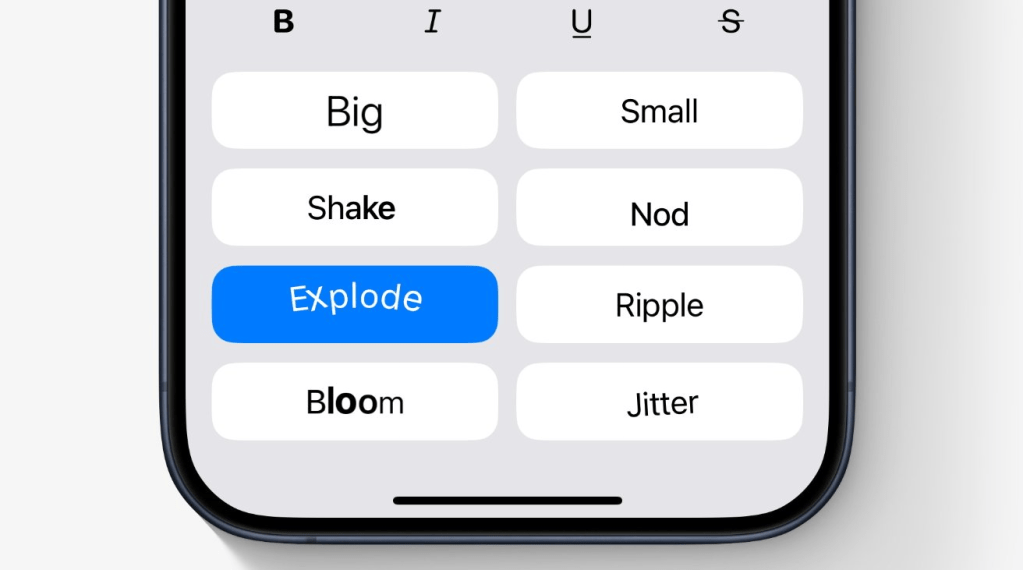

- When I say “Nooooooo” does my computer write “No!” or send with an Effect (iPhone – like Slam, Loud, Gentle,

- When I speak in a whisper, does my computer write in all lower case?

- When I laugh, does it insert a laughing emoji?

- When I speak in a little kid’s voice, does it write as if a 5 year old writes?

- When I shout, does it do all Caps?

- When I say “hmppff” does it recognize that as an expression of acknowledgement

- When I say “meowww” or other onomatopoeia, does it insert a cat emoji?

- When I gasp, does it write out “I’m incredibly surprised” or show a “Gasp” symbol?

- When I clear my throat, is there a

- When I enunciate greatly, does it leave more spacing or type in proper English? When I drawl or speak slang, does it translate to AAVE vernacular?

- When I sigh, does it write “sigh” or add a sigh emoji or find a few words to represent the emotional context?

I won’t try to propose a framework around figuring it all out. It will evolve as all shortcut standards have evolved – when it’s inserted by a forward thinking designer or developer, and that introduction meets adoption by users.

Whomever figures out voice shortcuts stands to own the voice operating system. Why? Translating voice to text is a form of data enrichment, and enriching data in a way that it becomes the new standard is a strong way to build moats, if you can maintain the association with being the inventor of the enrichment. See my prior post on sources of defensibility.

To effectuate this strategy most dominantly, the voice operator creating the standard would need to create a new visual element (something that can be read and identified as coming from their tool) that conveys the spoken emotion.

For example, Apple’s new text effects (released with iOS 18 in 2024) enabled individual word-based text effects that can be applied to specific words, things like Jitter. If I see a word exploding or jittering – I think Apple iMessage.

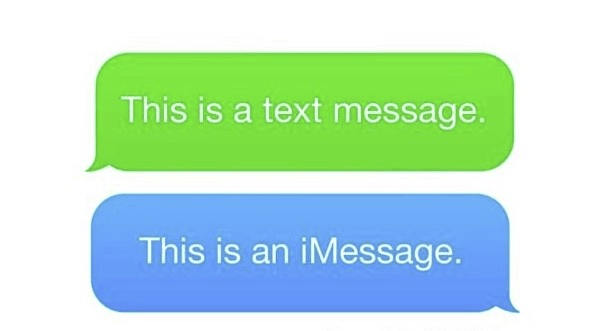

Apple also famously made texts within their ecosystem immediately recognizable with Blue Bubble and texts outside (with Android), Green Bubbles. This famous move quickly allows all iMessage users to identify people as in-network or out-of-network. Whomever owns voice could do the same – when messaging with someone who used voice shortcuts or buttons, you could identify them as having used a specific voice operating system.

I’ll caveat all of the above by highlighting that what I’m describing feels more like an intermediate solution to the existing display and computing paradigms available to us today – the laptop / desktop and mobile phone computer, where typing is the primary input.

I am excited about the potential for a leap forward to a new platform such as head-mounted glasses, but those feel further away (unless Meta-Ray Ban comes out with their screen this fall 👀).

Longterm, I could imagine that there is also Voice-to-Image, Voice-to-Video instead of just Voice-to-Text; but they’re beyond the scope of this article.

In Ted Chiang’s story, there’s a moment when Dr. Louise Banks realizes the heptapod’s language is not glottgraphic – meaning the writing doesn’t translate directly to speech. Instead, its semasiographic writing – “a written language that conveys meaning without reference to speech. There’s no correspondence between its components and any particular sounds.”

I realized AI doesn’t need the same language as us when I saw the video of two AI agents switching to a machine-only language called “Gibberlink” once they realized they were on a call with another agent.

The machines don’t need our language. It’s time we invented a new one. Voice is one of the exciting new frontiers where we can tackle this.

I’m excited to watch who cooks up voice buttons first.

Leave a comment